Series: Hear from the Experts

Families are Pivotal in Designing Math Picture Books for Children

How do you design a better picture book for children? What does better mean? How does consulting with families along with research help us to understand what makes educational children’s books effective and engaging? At our biennial conference Promising Math we discussed these questions.

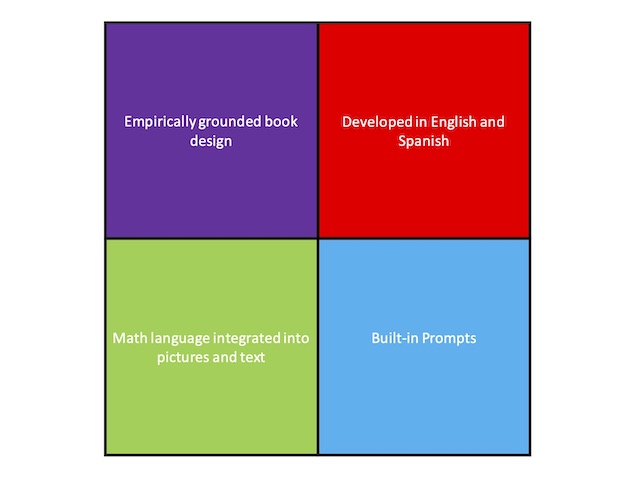

Keynote speaker David Purpura worked with colleagues at Purdue University and families in nearby communities to design children’s books that foster mathematical conversations at home (presentation PDF). His research has demonstrated the effectiveness of the books—children who used them at home learned more math-related language and improved their math achievement more than those who did not—but his presentation focused on the book development process itself. He commented, “If we go into this whole research process and find that something is really effective, but we haven’t considered the families and their ability to use it, and we can’t scale it… it’s kind of useless. It’s really important to consider families in the development process.”

One of the ways the project centered the families’ experience was to focus on a familiar activity, reading books together. Picture books tap into a practice that many families already have as part of their routine, rather than asking parents to do something completely new. David points out that “picture books can be this really great opportunity to… integrate math into homes.” Building on families’ love of reading together to add in talk about math seemed like a wise choice.

If we go into this whole research process and find that something is really effective, but we haven’t considered the families and their ability to use it, and we can’t scale it… it’s kind of useless. It’s really important to consider families in the development process.

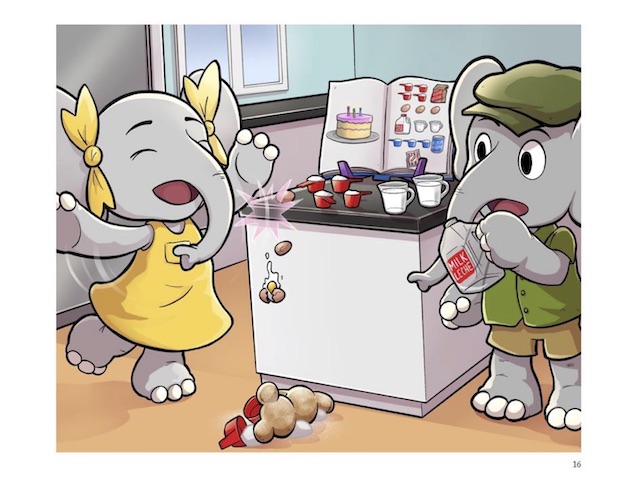

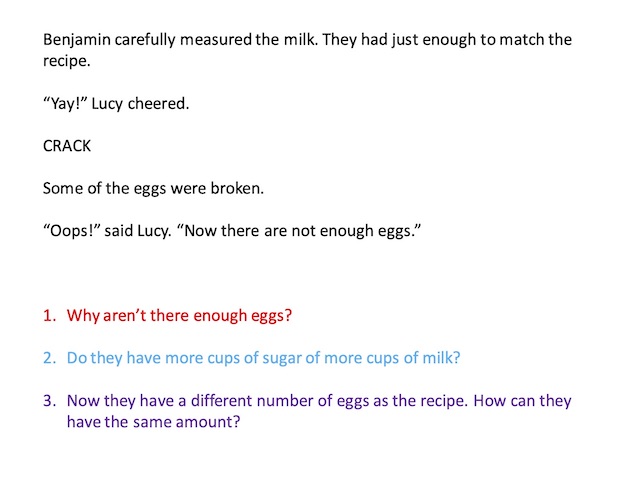

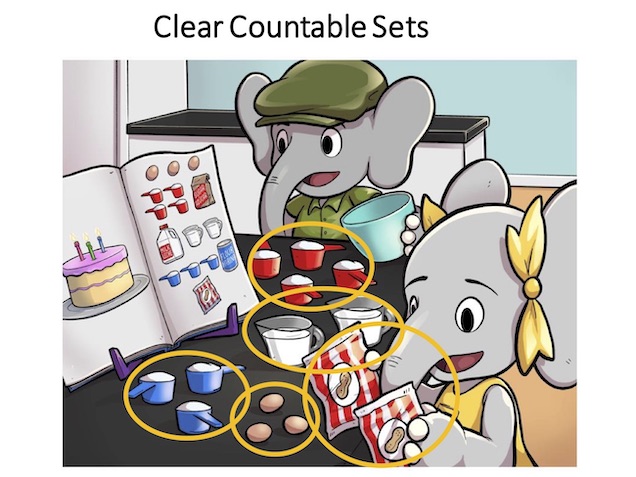

Second, the books include not only the text of the story, but example questions parents can ask about what is happening on each page. For example, when parents read a section in which the characters are talking about whether they have enough of each ingredient to make a cake, the extra text might suggest parents ask, “Why don’t they have enough eggs?” In this way, the book reading experience supports families to talk about what “enough” means, prompting math-related conversation at a developmental level just right for preschoolers. Each page includes three different questions, each just a little more complicated than the last, so children and caregivers can return to the book later and have a slightly different conversation. This thoughtful “scaffolding” of the reading experience makes it easy for parents.

Additionally, David’s team made the decision to write the books with both Spanish and English versions in mind from the very beginning. Often, books written in English translate poorly to Spanish, or they don’t account for that fact that different dialects of Spanish translate things differently. In one of the books, the authors changed the subject of the book from “too many marshmallows” to “too many pillows” because “marshmallows” can be translated to Spanish in at least 4 different ways, depending on dialect. David pointed out that there are around 40 million people over the age of 5 who speak Spanish in their homes, but the availability of children’s books in Spanish is low, and their cost tends to be higher than books in English, so the need for additional books in Spanish is real.

Most importantly, the development team involved families in the design at an early point in the process of the picture books for children. At first, parents came into their lab, read the books, and gave feedback. After a round of revision, parents were given three books and sent home with them for a month. They were asked to read the first book three times in the first week, the second book three times in the second week, the third three times in the third week, and in the fourth week, they read each one once more. The families were interviewed extensively about their experiences using the books. Researchers asked about both ease of use and enjoyment, making sure that the books might be something families would read again on their own. It was as a result of parent feedback that the team made all of the books bilingual—that is, the text and prompts are provided in both Spanish and English in every version.

It’s clear that involving parents as partners in designing the books helped make them effective tools for families to generate mathematically rich conversations. David points out, “…a brief intervention, 12 sessions of parents reading to their children, something they already do, was effective at improving children’s math language and numeracy skills, and the effects on numeracy were maintained over eight weeks after the intervention, and…the process was easy for parents to do.” David and colleagues are working with families to develop additional books that focus on spatial reasoning rather than numeracy, and hope to see similar results!

Family-Centered Approach to Picture Books with David Purpura

David Purpura describes his team’s research and intervention designed around picture books.

Family Math

Families can play a fundamental role in encouraging learning and interest in math. Explore all the resources in our Idea Library for Family Math.

Promising Math

Promising Math is a biennial conference that aims to share knowledge about the understanding, teaching, and learning of early math.